January 2026 – Edition 05

Cover Story

Reimagining Value and Impact in the Social Sector

A Digital Shift

In 1879, when the electric light bulb was first demonstrated by the prolific and evolutionary inventor Thomas Edison, the world did not immediately grasp the magnitude of the shift. It was not merely a better candle or just another tool for brighter illumination, but it was the introduction of the transformative power of electricity that would eventually reorganise society, industry, and daily life.

Today, the social impact sector stands at a similar juncture. We often view technology as a ‘better candle’ and think of it as a way to digitise a paper register or automate a manual report. However, genuine Digital Transformation (DT) is not fundamentally about tools, software, or automation. It is a profound shift in how organisations reimagine value, reorganise their models, and align their processes with their purpose.

Drawing on our experiences with population-scale platforms like Aadhaar and UPI, as well as deep implementation work with nonprofits, this article outlines why the sector must move beyond ‘tech-first’ thinking and adopt an unlearning-and-relearning mindset.

The Difficulty of Transformation: A Mindset of Vulnerability

Beyond the Tools: The Intellectual Structure of Transformation

To navigate this shift, we must first dismantle the terminology that often confuses the sector. There is a distinct hierarchy in how we engage with technology, and understanding this is crucial for leadership.

Defining the Shift: The Bread Analogy

Consider the simple act of buying bread to understand the three layers of digital change:

- Digitisation: This is converting the physical to the digital. If a shopkeeper scans a barcode instead of writing the price in a ledger, that is digitisation. It converts atoms to bits, but the process remains largely the same.

- Digitalisation: This involves improving existing processes using digital tools. If you order bread via an app instead of walking to the shop, you have digitalised the purchase. It offers convenience and efficiency, but the fundamental value proposition, that of selling a loaf of bread, has not changed.

- Digital Transformation: This is where reimagination occurs. If the bakery uses data to understand your consumption patterns and offers a bread subscription service and delivers fresh loaves to your doorstep, the business model has transformed. Or, perhaps they launch online baking classes to engage a community of home bakers. Here, the organisation is no longer just selling a product; it is selling an experience and a service model that was previously impossible.

The Framework: Purpose—Organisation—Technology

The most common error social purpose organisations (SPOs) make is starting with the tool. Leaders often ask, ‘How can we use AI?’ or ‘Which software should we buy?’

A different approach is what is needed: The Purpose—Organisation—Technology triangle.

- Purpose: The journey must begin here. What is the specific capability we are trying to improve?

- Organisation: How are we organised to deliver that purpose? Do we have the capabilities, beyond just the positions or hierarchy, to execute this vision?

- Technology: Only once the purpose and organisational capabilities are defined should technology enter the conversation as an enabler.

Rethinking the Value Chain

Transformation requires us to analyse our value chain, which is the set of activities that deliver value to the beneficiary

Transformation requires us to analyse our value chain, which is the set of activities that deliver value to the beneficiary.

Consider the evolution of Aadhaar. When the project began, initial proposals suggested replicating the Election Commission model: thousands of staff and offices across India. This would have been a linear scaling of an existing model. Instead, the leadership reimagined the value chain. They separated the question ‘Who are you?’ (Identity) from ‘Do you deserve this benefit?’ (Entitlement).

By focusing solely on creating a unique digital identity that other institutions could build upon, Aadhaar became a foundation for transformation, enabling everything from Direct Benefit Transfers to the UPI ecosystem. This was not a ‘better identity’ document; it was a fundamental reimagining of how a state interacts with its citizens.

How Reimagining Value Can Help SPOs

Why go through this difficult process of reimagining the value chain? Because the opportunities for SPOs go far beyond simple efficiency. There are three specific areas where digital shifts the paradigm.

Early Warning Systems: Instead of waiting for an annual report to find out a program failed, digital systems provide real-time alerts. If a child’s weight drops, the system flags it immediately, allowing for course correction before it’s too late.

Accountability and Governance: Technology improves transparency. The system, for example, can reveal whether the field coordinators are actually visiting the field. This transparency ensures resources actually reach beneficiaries.

Ease of Telling the Story: Donors need more than anecdotes; they need hard facts. Data allows you to tell a convincing story of impact and efficacy, which is critical for fundraising.

From Theory to Practice: The Five Pillars of Execution

While the strategic mindset is vital, the ‘how’ of transformation is where the rubber hits the road. For many SPOs, the reality is messy. Field workers are often burdened with data entry rather than counselling, teams plan visits based on intuition rather than insight, and programs struggle to scale because information is trapped in spreadsheets and notebooks.

To bridge the gap between high-level strategy and on-ground reality, the following five pillars of the digital transformation journey are to be considered:

- Designing for DT: Defining the problem with a magnifying glass.

- Systems and Processes: Re-engineering workflows rather than automating inefficiencies.

- Applications and Building: Selecting the right partners and building modular solutions.

- Implementation and Rollout: Managing the ‘go-live’ and ensuring stability.

- Capacity Building: Training and driving adoption.

The FMCH Experience: A Case in Point

The experience of the Foundation for Mother and Child Health (FMCH) offers a powerful illustration of these pillars in action.

FMCH works to combat malnutrition and improve maternal health. Their model relies on field workers visiting families to provide counselling. Initially, the problem appeared to be data management. Workers were spending too much time filling out physical registers or Excel sheets.

However, a deeper diagnostic revealed that the core challenge was not just data entry; indeed, it was decision-making.

- The Planning Problem: A field worker manages 200 families. How do they decide whom to visit today? Often, they would visit those geographically closest, potentially missing a high-risk mother or a malnourished child.

A critical lesson as much from the FMCH case as from many others is that technology must be designed for the user on the ground, not just for the dashboard in the head office.

- The Consistency Problem: How do they ensure that every worker provides the correct, medically accurate advice during a visit?

The Solution: FMCH did not just digitise their registers. They built an app called Nutri that fundamentally altered the workflow. - Decision Support: The app included a decision tree. Based on the data entered (e.g., child’s weight, age), the app guided the worker on exactly what questions to ask and what counsel to provide.

- Smart Scheduling: The system automatically prioritised visits. Workers could see a list of due and overdue visits, ensuring that high-risk cases were never missed.

- The Impact: The results were transformative. Planning time for field workers dropped from one hour to five minutes. Missed visits plummeted. Most importantly, field workers could now handle 350–400 families instead of 200, effectively doubling their capacity without doubling the stress.

Design Principles: Build for Users, Not Dashboards

A critical lesson as much from the FMCH case as from many others is that technology must be designed for the user on the ground, not just for the dashboard in the head office.

There is often a disconnect between the ‘backend’ (finance, HR, donor reporting) and the ‘frontend’ (program delivery). While backend efficiency is important for compliance, the frontend is where the impact multiplier lies. A finance system helps you report better; a program system helps you serve better.

When designing these systems, we must resist the allure of the ‘Super App’. There is no single software that can handle payroll, fundraising, and field operations for every nonprofit. The diversity of programs, from education to healthcare to livelihoods, requires modular, adaptable solutions.

Adoption, Culture, and the Joy of Implementation

Finally, we must recognise that digital transformation is, at its heart, a people project. Technology fails when it is imposed; it succeeds when it is embraced.

This requires a cultural shift in how we view implementation.

- The Joy of Rollout: Launching a new system should not be a mundane administrative update. It should be celebratory, like a formal launch event with virtual ribbons, cakes at field offices, and videos from leadership. This signals to the team that the new tool is an investment in their success, designed to make their lives easier and their work more impactful.

- Data Empowerment: In the traditional model, data flows upward to satisfy donors. In a transformed organisation, data flows downward to empower workers. When a field officer can look at an app and say, ‘I know I have achieved 60% of my targets and need to focus on the remaining 40%,’ they move from being data-entry operators to decision-makers.

The Path Forward

Digital transformation is not a destination; it is a journey of milestones. It requires the courage to unlearn old ways of working and the patience to build capacity, step by step.

The ultimate measure of this transformation is leverage. Leaders should ask themselves: For every unit of change in digital capability, what is the change in organisational capability? If we are merely buying tools, the leverage is low. But if we are reimagining how we identify a beneficiary, how we deliver training, or how we monitor outcomes, the leverage can be exponential.

As we look to the future, let us not settle for a ‘better candle’. Let us have the ambition to flip the switch, for the needs of the millions we serve are too urgent and too vast for incremental fixes. The moment calls not for small improvements, but for bold, systemic transformation.

Rekha Koita

Co-founder & Director, Koita Foundation

Rekha Koita is the director and co-founder of the Koita Foundation which focuses on two key areas: digital health adoption in India and the transformation of social purpose organisations (SPOs). With consulting experience at Accenture and a corporate training background at Mind Matters, Rekha spearheads the SPO transformation efforts.

The foundation works with SPOs to optimise processes and implement technology to enhance program scale and outcomes.

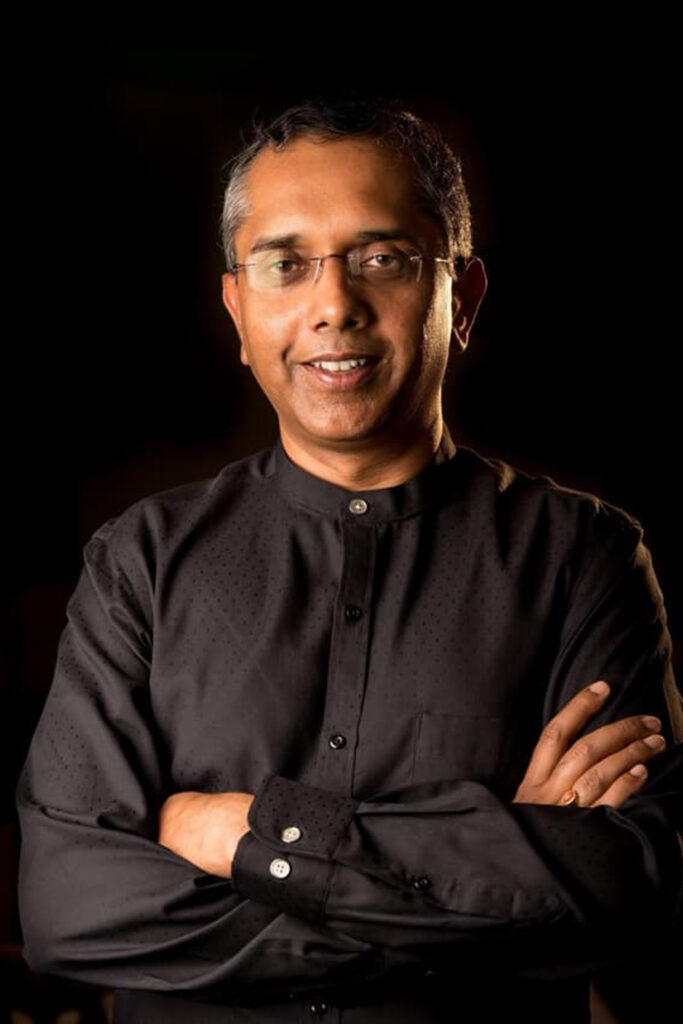

Shankar Maruwada

Co-Founder & CEO, EkStep Foundation

Shankar Maruwada, CEO and co-founder of EkStep Foundation, combines his passion for solving largescale social challenges with the power of technology. An accomplished entrepreneur and marketing leader, he brings deep expertise across domains and has played a key role in transformative initiatives such as Aadhaar—India’s national identification program—where he led demand generation and marketing. Previously, Shankar co-founded Marketics, one of India’s pioneering data analytics firms. He continues to support the startup ecosystem as an investor and mentor.

Copyright © 2026 India Leaders For Social Sector