January 2026 – Edition 05

Guest Column

From Compliance to Cultural Change: Understanding the Relevance of Personal Data Protection

Deepika Mogilishetty

Chief - Policy & Partnerships, EkStep Foundation

India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP Act), which took effect on 13 November 2025, marks a decisive shift from ad hoc data practices to a rights-based legal framework. For social sector organisations working directly with vulnerable communities, the law is not merely a compliance exercise; it is a call to build new habits of care and prudence. The next 18 months, before full enforcement in May 2027, offer a strategic window to embed those habits, rather than to defer action until penalties loom.

In this article, we explore crucial and practical approaches organisations can take to build data protection practices and ensure their operations are resilient as well as compliant.

Beyond Checkboxes: Cultivating Compliance as Practice

The DPDP Act foregrounds principles that require behavioural change: informed, specific, and unambiguous consent; purpose limitation; data minimisation; accuracy; storage limitation; security; and accountability. The high financial penalties anticipated under the Act are meant to signal seriousness, yet their true value will be realised only if organisations translate legal obligations into everyday practice. In this sense, data protection should be approached much like workplace safety or the Prevention of Sexual Harassment (POSH) rules: a matter of organisational culture, not a legal checkbox.

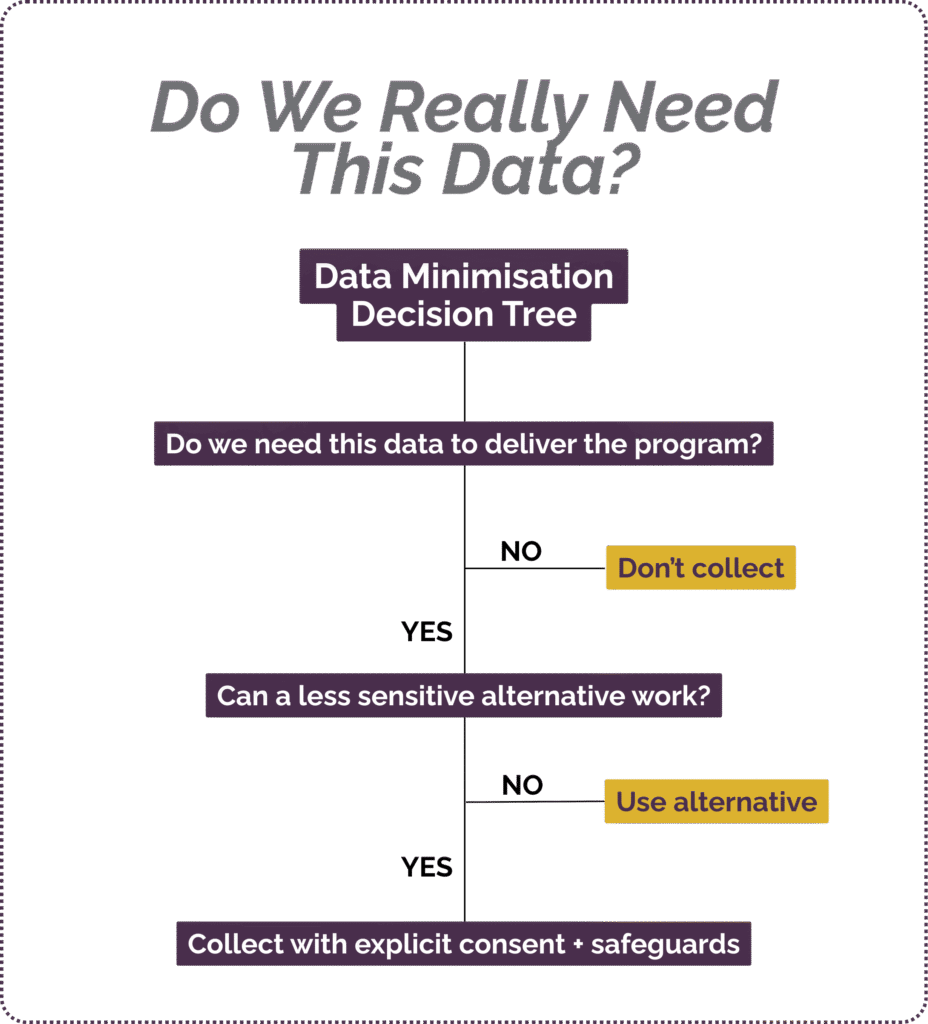

Data Minimisation: Less is More

A practical starting point is data minimisation. Organisations must routinely ask whether a data point is truly necessary. For example, do field intake forms require an exact date of birth, or would an age band suffice for program eligibility? Reducing unnecessary collection lowers risk and simplifies consent. Managers, not only legal teams, must be empowered to question long-standing data practices and to approve simpler, safer alternatives. Not surprisingly, this also reduces the cost of data collection, storage and maintenance, especially for NGOs who are already resource-constrained.

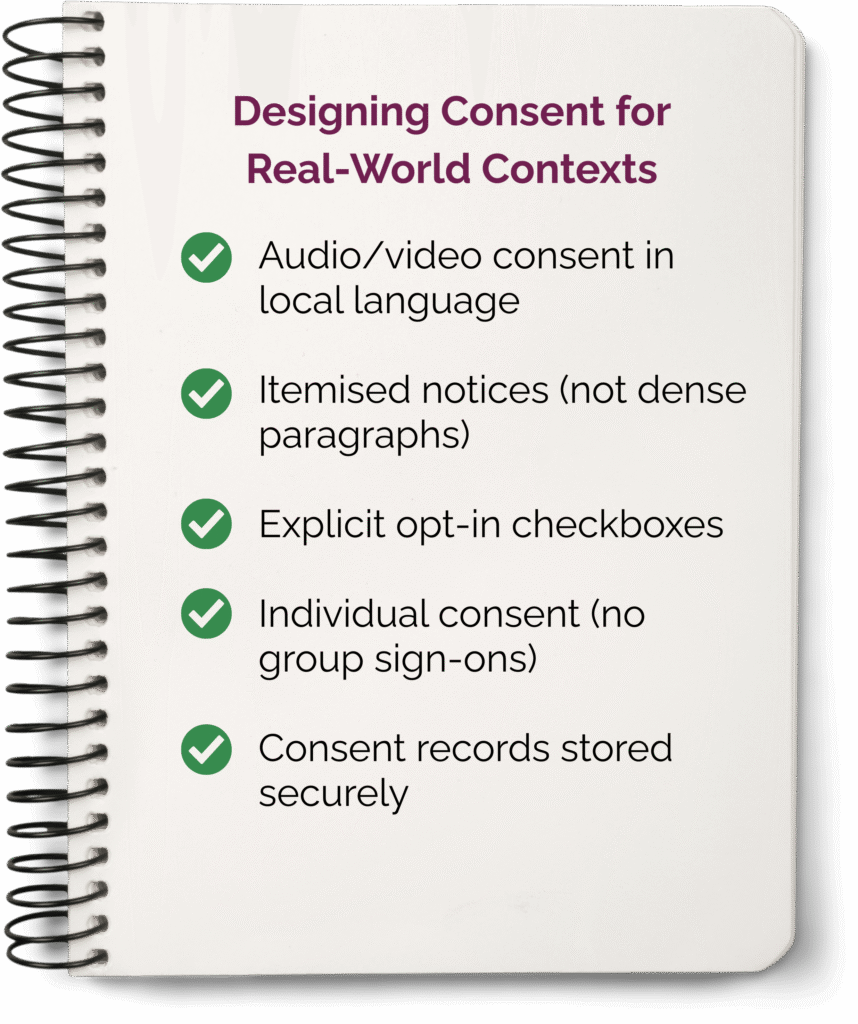

Inclusive Consent: Bridging Barriers

Obtaining informed consent in low-literacy, multilingual, or emergency contexts is a recognised operational challenge. The law requires consent to be free, specific, informed, and unambiguous, and organisations should adopt practical adaptations: audio or video explanations in local languages, itemised notices rather than dense legal text, and visible checkboxes for explicit consent on digital forms. Group sign-ons should never substitute for individual consent when personal data is involved. Organisations must also retain records of consent as demonstrable evidence of compliance.

Special Care: Protecting Children’s Data

The DPDP Act treats the data of individuals under 18 with heightened sensitivity. Verifiable parental or guardian consent is mandatory, alongside stricter limits on behavioural tracking and profiling. Nonprofits working in education, child protection, and health must design consent pathways that are verifiable and age-appropriate, and they should define clear deletion or transition practices for data when a child reaches adulthood.

Vendor and Donor Relationships: Contractual Safeguards

External tools, SaaS vendors, and donor reporting requirements introduce distinct risks. Contracts should include explicit data protection clauses, with defined roles as either data fiduciary or processor, mandate breach notification and specific data retention and residency/localisation processes. For vendors hosting servers abroad, organisations should require demonstrable legal and technical safeguards, and avoid assuming that consent gathered by a third party is sufficient without verification.

Breach Readiness: 72 Hours to Act

Organisation Ownership: Privacy as a Habit

Embedding data protection requires cross-functional ownership. Legal and IT teams cannot carry the burden alone; program managers, field staff, communications teams, and senior leadership must be trained to recognise data risks and to follow simple, consistent workflows. Regular training, accessible notice-and-consent templates, vendor due diligence checklists, and a clearly assigned grievance redressal mechanism will convert legal requirements into everyday practice.

The Implementation Runway: Act Strategically

By prioritising data minimisation, designing credible consent processes, securing vendor contracts, and practising breach readiness, organisations can turn regulatory obligation into a competitive advantage

Deepika Mogilishetty

Chief - Policy & Partnerships, EkStep Foundation

Deepika Mogilishetty is the Chief of Policy and Partnerships at EkStep Foundation, where she has been since 2014. She is a lawyer whose journey across law, human rights and public policy, and technology has always been anchored in questions of inclusion and justice. She has worked on issues such as the right to information and women’s access to justice, and on core digital infrastructure like Aadhaar.

At EkStep Foundation, her work continues to be about creating possibilities— hether through digital public goods for learning or through initiatives in the early years that celebrate abundance and potential in every child—Bachpan Manao. Across all of these, her core belief has remained the same: law, policy, and especially technology must serve human dignity, expand agency, and open doors for equitable access for all.

Copyright © 2026 India Leaders For Social Sector