Ocotber 2025 – Edition 04

ILSS Conversation

Strengthening Systems, Deepening Impact: Reimagining Foundational Learning in India

In a recent webinar on ‘The Social Sector: Then and Now,’ organised by the ILSS Centre of Excellence for Board and Governance, ILSS Founder-CEO, Anu Prasad, engaged in a compelling conversation with Dr Dhir Jhingran, Founder and Executive Director of the Language and Learning Foundation (LLF). A former IAS officer, Dr Jhingran has served in senior policymaking roles at the Ministry of Education, as senior adviser to UNICEF India, and as Regional Director with Room to Read, in addition to authoring several books on primary education. Through LLF, he is working to strengthen foundational learning at scale by working closely with governments across India. The dialogue explored his journey from policymaker to social entrepreneur, LLF’s systemic approach to education reform, and the governance lessons that can guide organisations in the sector. Here are some edited excerpts from the conversation.

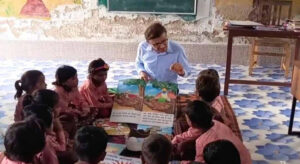

The Language and Learning Foundation (LLF) works with government education systems to strengthen Foundational Literacy and Numeracy (FLN) among children. LLF trains and supports teachers, mentors, and officials in child-centred practices and develops contextually relevant materials, including multilingual and local-language resources. Since 2015, LLF has partnered with 10 state governments to integrate foundational literacy into government programs, reaching 1.62 crore children and 10.85 lakh teachers.

Founder and Executive Director, Language and Learning Foundation (LLF)

Anu: Your transition from government roles to founding the Language and Learning Foundation is exceptional. What led you to set up the foundation?

Dhir: I developed a deep interest in education during the total literacy campaigns of the 1980s and 90s. Watching children remain passive while teachers delivered long lectures convinced me that something was fundamentally wrong with our methods. Within the IAS, I deliberately sought education postings, leading the District Primary Education Program, serving as state education secretary, and working in the Ministry of HRD. But given the frequent rotations across sectors, I eventually faced a choice: move to other departments or commit fully to education. I chose the latter and founded the Language and Learning Foundation (LLF).

Our organisational design reflected three strategic principles: an exclusive focus on foundational learning where gaps were largest, a commitment to scale, and government collaboration as our primary approach for systemic impact. Today, LLF operates across 10 states, engaging in traditionally government-held domains such as curriculum design, teacher training, and assessment systems, moving beyond program delivery to actual program design and systemic strengthening.

Anu: From the very beginning, you chose to work with the government, even when many nonprofits preferred to operate in parallel. How has that journey unfolded?

Dhir: In 2015–17, very few organisations engaged directly with government systems, so we had to approach state governments proactively. We chose professional development as our entry point, which gave us access to run courses and training programs. As the sector matured, we built coalitions, recognising that lasting solutions required collaborative governance.

With the launch of NIPUN Bharat in 2021, governments became more proactive in seeking partnerships with civil society not just for delivery, but also for program design, curriculum development, training, and assessments. Over time, we reintroduced demonstration programs to show how governments could drive learning improvements themselves at the district level, while also experimenting with innovative financing models like outcome-based funding and impact bonds.

Anu: Is there any unique governance role social purpose organisations can play that the government cannot?

Dhir: The governance landscape has shifted fundamentally. Earlier, civil society organisations worked in specialised niches; today, with CSR funding and a proliferation of players, the ecosystem is crowded, with many organisations now having government MOUs. This raises key questions of coordination and duplication. The real demand now is for organisations that not only deliver outcomes but also strengthen systems. The highest value nonprofits can bring is this dual mandate: measurable impact combined with building government capacity for sustainable change.

Anu: As a founder, what were your biggest organisational challenges in building LLF, particularly the governance and systems aspects, besides the programmatic work?

Dhir: Our biggest challenge has been preserving organisational DNA while scaling from 200 to 600,000 teachers, maintaining quality and mission-driven rigour and not losing what made us effective in the first place. We have had to develop sophisticated governance systems, including operational protocols, field checklists, and internal accountability measures, to ensure that everyone works within the same institutional standards.

The second challenge has been navigating continuity in government partnerships through constant changes in political leadership. We learned that sustainable partnerships require building professional relationships across all levels, like block, district, and mid-tier officials, who provide institutional memory when political leadership shifts. This multi-level relationship strategy demands significant investment but proves essential for program continuity.

Anu: With operations across 10 states, what is your expansion governance strategy — broader reach or deeper engagement

Dhir: Expansion decisions are complex, especially in large states like Uttar Pradesh that demand long-term commitment. Our core principle is to never voluntarily exit a state and to prioritise depth over breadth.

We follow three criteria: avoiding oversaturated states where many organisations compete; ensuring new expansion does not compromise the quality of existing programs, which makes us conservative about growth; and targeting educationally disadvantaged districts with marginalised populations.

This values-driven approach explains our strong presence in the tribal areas of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Odisha. Every expansion is carefully deliberated, weighing impact potential, relationship-building capacity, and alignment with our mission to serve marginalised communities.

Anu: LLF has a diverse governance structure with trustees, an advisory board, and other guiding groups. How do you manage this complexity while staying aligned to your mission?

Dhir: Our structure is by design. Trustees handle legal compliance while providing strategic direction. The advisory board was our strategic innovation, purely advisory but serving critical functions: domain expertise, networks, credibility, and strategic counsel. It took us three years to establish, focusing on education professionals with government experience and leaders skilled in scaling without compromising quality.

Our strong organisational vision ensures all discussions remain anchored to our foundational scope. While board members may suggest new directions, debates stay productive because the mandate is respected. We welcome disagreements for sharper decisions, but final authority rests with the organisation. By maintaining clear boundaries between advisory input and executive decisions, we turn diversity into a strength, with each member bringing complementary perspectives to strategic thinking.

Anu: Have you considered board tenure policies, given that many governance experts recommend term limits?

Dhir: We have wrestled with the continuity versus renewal governance dilemma. We extended our initial board tenure once, requesting that all members continue, as we were at a critical organisational inflection point, expanding operations and deepening government system engagement, where institutional memory was invaluable.

We have added new members over recent years to add new expertise in corporate strategy, communications, and education technology as needs evolved, while maintaining core continuity. Some existing board members occasionally suggest stepping down to make room for new talent, but we have prioritised institutional continuity until now. We may reassess this approach as we mature institutionally

Anu: Beyond quarterly meetings, how do you maintain continuous board engagement throughout the year

Dhir: We go beyond formal meetings by making board engagement immersive. Our meetings are often three-day sessions in operational states with field visits, turning members into informed stakeholders who see ground realities firsthand. We also integrate our senior leadership team into board interactions, enabling direct engagement, informal mentorship, and the flow of expertise across the organisation and not just to the founder.

We also learned that board engagement works best when it grows organically. Early on, we tried a mechanistic approach — mapping expertise to needs on spreadsheets and making targeted requests — but it felt forced and was ineffective. The most impactful contributions have come voluntarily, through relationships. For example, one board member independently led our complete rebranding strategy.

We now focus on creating space for such organic engagement while strategically leveraging members’ networks for government introductions, corporate partnerships, or navigating bureaucratic hurdles. The key is timing: most members are eager to contribute, so the challenge lies in aligning their expertise with institutional needs at the right moment.

We now focus on creating space for such organic engagement while strategically leveraging members’ networks for government introductions, corporate partnerships, or navigating bureaucratic hurdles

Anu: What process do you follow while onboarding new board members?

Dhir: We recognise our onboarding is still evolving, but our strategy includes one-on-one orientations with detailed materials, followed by field visits and direct team interactions. Field exposure is critical, as boardroom discussions often differ greatly from ground realities.

We also dedicate meeting time to contextualising discussions within program frameworks. This may limit deep strategic dives, but it ensures board members give relevant, grounded guidance rather than generic advice.

Anu: What advice would you offer to senior leaders considering joining the boards of social purpose organisations?

Dhir: Effective governance begins with preparation. First, understand both the nonprofit ecosystem and the organisation’s sector and refrain from demonstrating immediate impact until you grasp institutional dynamics. Second, engage with existing board members to learn unspoken governance norms. Third, build relationships beyond the founder by meeting senior staff. And fourth, prioritise field exposure to understand implementation realities.

The most effective board members identify a clear niche for their contribution rather than trying to influence everything.

The most effective board members identify a clear niche for their contribution rather than trying to influence everything. Patience, coupled with systematic institutional learning, is essential before making strategic contributions.

Anu: What is your dynamic with your board chair, and how do you manage that governance relationship?

Dhir: Our board chair is a distinguished leader in the education sector. We anchor our governance relationship through transparency and consultation, briefing her thoroughly before meetings, walking through agenda items so she is well-prepared for strategic discussions. Her input is especially valuable when considering new board members, where she is our first point of consultation.

At the same time, our governance culture is intentionally non-hierarchical. In meetings, everyone contributes equally, enabling reflective and open discussions rather than top-down dynamics. Advance briefings simply ensure smoother facilitation while preserving this collaborative spirit.

Anu: What systemic gaps do you see that could help make the development sector more effective?

Dhir: I see two major governance gaps: lack of coordination and short-term thinking.

On coordination, most organisations approach governments with their own agendas, which often creates lack of clarity on programmatic and implementation focus. What’s needed is for governments to exercise their convening power in setting a clear direction and inviting organisations to plug in with specific expertise.

On short-term thinking, the pressure for quick results undermines sustainability. Even NIPUN Bharat expects proficiency within a few years, but lasting impact requires strengthening the autonomous capacity of government systems. Civil society should support this development, not substitute for this goal.

The proliferation of project management units (PMUs) is another concern. Uttar Pradesh alone has more than a dozen, but unless they build lasting state capacity, they risk leaving institutions weaker once projects end. This is a fundamental governance question: are we building resilient systems or fostering dependency? To address it, the sector needs stronger leadership development infrastructure so founders can navigate these institutional challenges effectively.

Anu: What essential leadership qualities are critical for sector leaders today in building resilient, sustainable organisational impact?

The biggest challenge for sector leaders is defining success. Growth metrics — bigger budgets, larger teams, wider reach — can easily distract from the core purpose. The real question is: what are we actually changing for children, teachers, and other stakeholders beyond the numbers? This calls for leaders who prioritise stakeholder experience over evaluation reports, taking the time to understand how beneficiaries truly feel about the interventions.

Three essential leadership qualities stand out:

First, strategic thinking with five-year horizons. Leaders must analyse atleast shifting policies, ecosystems, and competitive landscapes to avoid reactive decisions and position their organisations proactively.

Second, organisational nimbleness. With rapid environmental change, leaders need to respond thoughtfully to government shifts and stakeholder feedback and evolve steadily without sudden, dramatic changes.

Third, dual competency. Effective leaders combine strategic vision with deep operational understanding. By understanding practices like teaching methodologies, they can connect authentically with staff and bridge high-level vision with on-ground execution.

Anu: As someone who has been a policymaker, practitioner, and founder, what gives you hope for the future of governance in the social sector?

Dhir: My optimism comes from looking for signs of institutional change. While overall system indicators may not always look transformative, there are consistent bright spots that show progress.

One example is the current high-level focus on student learning outcomes. A decade ago, it was hard to even start that conversation with governments. Learning was not prioritised. Today, it is central to governance discussions, marking a fundamental shift.

I also draw hope from grassroots perspectives, from teachers, parents, and communities describing the changes they see and feel. Large-scale evaluations often miss these voices, but they provide powerful evidence of institutional evolution.

Staying directly connected with schools and communities provides authentic feedback on governance transformation, offering insights that data alone often misses. While quantitative metrics may show only modest improvements, community voices frequently highlight significant institutional transformations in their daily experiences.

Hope, for me, lies in this combination of systemic policy change and grassroots transformation stories. Together, they provide a fuller picture and sustain long-term commitment to institutional change.

Copyright © 2024 India Leaders For Social Sector